November 2025

Michael Galley

Share

Online Experiments for Consumer Protection and Competition Law

Around the world, regulators are beginning to pursue legal action against companies that use dark patterns and design to deceive and exploit consumers illegally. For instance, Amazon recently settled with the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for a record $2.5 billion after allegedly tricking consumers into signing up for Prime subscriptions that were excessively hard to cancel, and, in the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has launched court action against Emma, a mattress company, over misleading discounts and urgency claims. Additionally, legislators are working to address emerging harmful practices. To inform enforcement cases and new regulatory frameworks, regulators need reliable evidence of harm, which is currently scarce. Incentive-compatible, high-fidelity online experiments can provide this evidence.

What practices are we talking about?

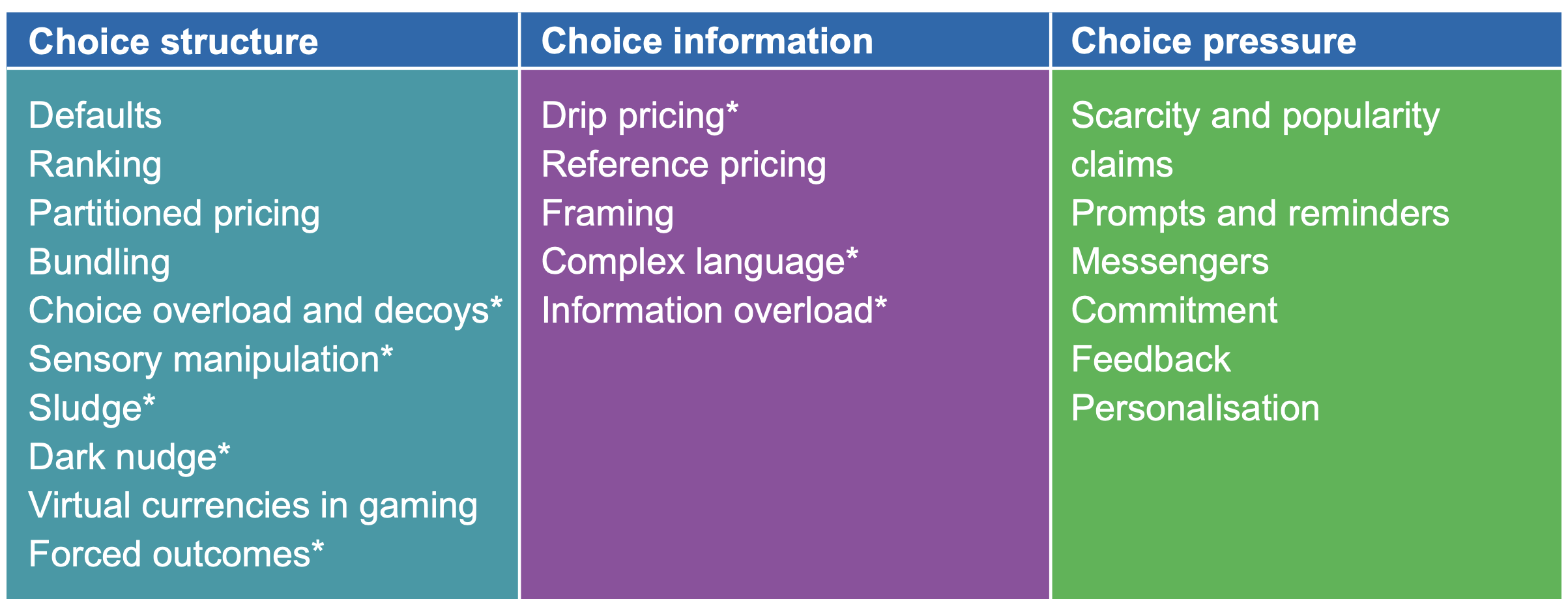

The design of digital interfaces and how choices are presented affect the behaviour of users. Interest in this phenomenon, known as online choice architecture (OCA), is growing, particularly among regulators who are concerned that certain OCA practices are used to illegally harm consumers and reduce competition. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has published a taxonomy of OCA practices outlining how various practices cause potential harm.

Within the taxonomy, the CMA distinguishes practices considered always harmful (marked with an asterisk in the above table (e.g., sludge, dark nudge, drip pricing) from those that cause harm in certain circumstances but not always (e.g., defaults, reference pricing, prompts and reminders). This distinction is crucial. Often, whether or not a practice causes harm is situation- and context-dependent. Therefore, rather than creating legislation that bans a practice outright, it may be better to monitor individual cases where it is breaching existing legislation and harming consumers.

What are the types of harm?

The two main categories of harm that OCAs cause can be described as:

- Direct Consumer Harm: Using manipulative design to undermine consumer autonomy and cause them to make choices or spend more than they would if they received clear, honest information. Typical harms include financial loss, loss of autonomy, privacy violations, and time and frustration costs.

- Market-level harm: Practices that make it unnecessarily difficult for consumers to switch between companies or compare options. This reduces competition between businesses and prevents consumers from choosing better alternatives.

Direct consumer harm is covered by consumer protection law, while market-level harm falls under antitrust and competition law. Still, there are many overlaps between the two, for example, anti-competitive practices often also harm consumers. As a prominent illustration of this, budget airlines set very low initial prices and then use drip pricing to increase them (charging extra for luggage, seats, etc.), making it difficult for consumers to compare with other airlines’ offerings, whilst deceiving them during this purchase decision. For more details on this example, read our recent newsletter on how deceptive design triples flight costs.

Current state of legislation

Existing legislation prohibits these types of harm, but it is generally not explicit in specifying exact practices that are illegal or in outlining how to identify them. For example, the US FTC Act prohibits ‘unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting Commerce’ and the EU Digital Services Act (DSA) states that ‘providers of online platforms shall not design, organise or operate their online interfaces in a way that deceives or manipulates [users]’. In 2021, the FTC issued an enforcement policy statement warning businesses that any use of dark patterns to “trick or trap” consumers is a violation of the FTC Act. The UK’s 2024 Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act (DMCC) was novel in blacklisting several practices, including drip pricing, fake or misleading reviews, and misleading scarcity claims. In many instances, however, legal action against companies requires explicit proof that consumers are being manipulated or deceived by the practice in question, and ideally, it quantifies the harm being caused.

Enforcement and new regulation require evidencing and measuring harm

There may be several cases where behavioural insights from other contexts suggest or can be used to make an argument that a practice causes harm. However, given the influence of context on behavioural effects, these arguments are insufficient to charge companies with breaching existing consumer or antitrust legislation, or to design new laws. For that, substantial evidence is required. A few examples of this are:

- What is the effect of long or complex tariff options on decision-making, especially for vulnerable consumers?

- How do defaults and pre-selected options impact consumer choice across markets like broadband, insurance, and streaming?

- How does the layout and format of consent information influence understanding?

High-fidelity online experiments can provide this evidence

Ideally, the evidence is gathered from organisations themselves through internal A/B or UX tests. If these exist, they can be subpoenaed. For example, the FTC obtained internal evidence from Epic Games, the makers of Fortnite, that showed how their user interface design and billing flows (such as confusing button placement, minimal or no purchase confirmation, default saved credit-card use, and frictionless purchases) led to unwanted and unauthorised in-game spending. The company settled, agreeing to pay $245 million in customer refunds.

The problem is that obtaining this type of data is not always feasible. A proven solution is to create highly realistic simulations of the platform in question and conduct a randomised controlled experiment to measure the effect an OCA practice is having. These experiments must be ‘incentive-compatible’ to ensure that the decision-making of experiment participants is reflective of “real” consumers. The high-fidelity nature of these online experiments enables the reliable collection of evidence that measures precisely how consumers’ behaviour is affected by certain practices, and therefore measures the harm to consumers or distortion to fair competition. These results can contribute to enforcement by establishing and quantifying damages. Our blog on innovative online experiments provides a more detailed explanation of this methodology.

The value of simulation experiments is well-established in the realm of consumer protection, particularly as a tool to inform policy development and regulation. The CMA praises their ability to ‘produce evidence that would not otherwise be available’, and the FCA believes they will ‘play a big part in improving consumer outcomes’ in years to come. Such experiments have been used by the Federal Trade Commission, the European Commission, the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), and the Consumer and Markets Authority (CMA). However, they are yet to penetrate the enforcement side of consumer protection by being used to generate case-specific evidence of harm. Given that courts regularly accept evidence from similar but less robust forms of online experiments (like non-simulation discrete choice experiments), these experiments offer great potential to regulators trying to enforce consumer protection laws.

The Behaviouralist has helped to pioneer this methodology, running high-fidelity simulation experiments for consumer protection organisations including Citizens Advice and Which?. Our recent work with Citizens Advice (to be published soon) investigates how various OCAs impact vulnerable consumers. We generated realistic marketplaces that consumers used to perform shopping tasks such as purchasing a broadband plan, choosing a gym membership, and booking a hotel room. We then measured how different product choice screens with reference pricing, sensory manipulation, and time-limited discounts affected their behaviour. Our experiment for Which? measuring the impact of fake reviews on consumers using a replication of the Amazon website was cited by the FTC as the ‘most direct estimate of welfare losses from review manipulation’. We have also run several high-fidelity simulation experiments for organisations like Open Banking and Mozilla.

If you are interested in working with us to generate high quality evidence to inform or enforce regulation, please don’t hesitate to get in touch!