4th August 2021

By JingKai Ong

Our COVID-19-related work

Many organisations around the world were forced to close their offices and have their staff work from home due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The Behaviouralist is no exception: we closed our London office in March 2020 and our team has since been working remotely. Despite various challenges during the pandemic, we were fortunate to be able to continue our work and mission in promoting positive behaviour change.

In this blog post, we offer a glimpse into some of our COVID-19-related projects and share two key insights we have learned through them.

1. Behavioural interventions can help encourage the adoption of protective health behaviour, but they may have unintended consequences.

At the onset of the pandemic, we conducted two online experiments and found important evidence that behavioural interventions can be used to positively change behaviour in a low-cost and scalable way to control the spread of the virus.

In the first experiment, we assessed the relative effectiveness of two COVID-19-related information interventions: 1) an intervention that emphasises the risk that the virus poses to individuals (the ‘personal intervention’); and 2) an intervention that emphasises the risk that the virus poses to friends and family (the ‘friends-and-family’ intervention). We also evaluated whether adding a statement that frames non-compliance with social distancing as an active choice improves the effectiveness of the interventions.

We found that both information interventions positively change behaviours but in different ways. For example, the personal intervention makes people more likely to access high-quality information about the pandemic, while the friends-and-family intervention makes people more likely to pledge to follow the World Health Organization’s advice and to state that they would avoid visiting those in high-risk groups. We also found that the active choice statements encourage compliance with social distancing and appear to be more effective for those who have an aversion to actively causing harm.

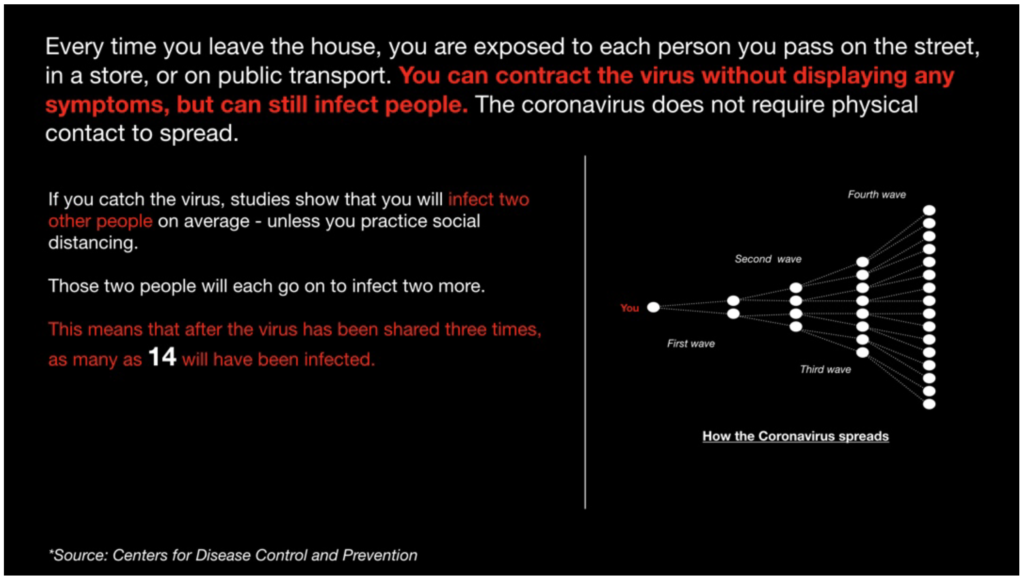

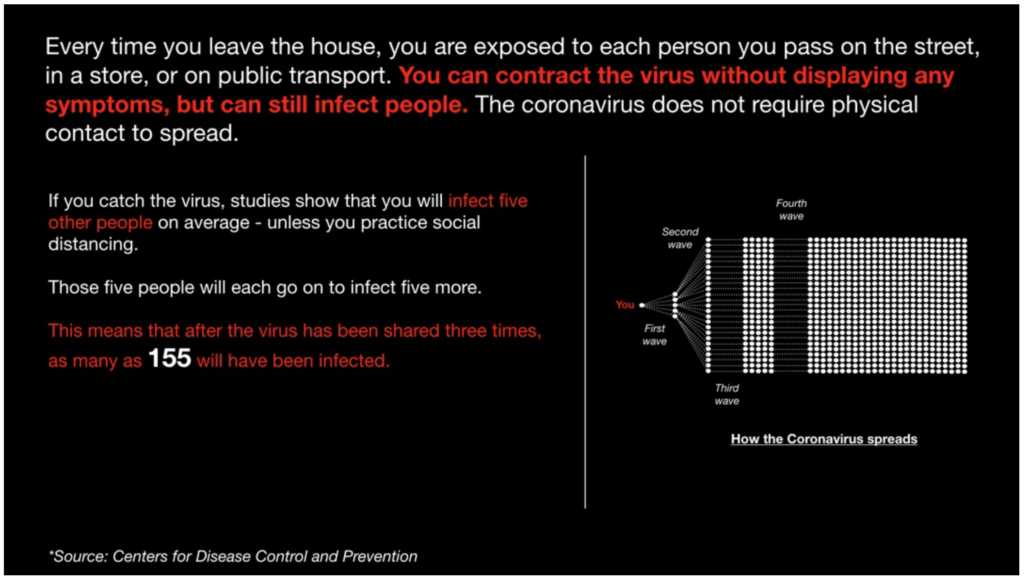

In the second experiment, we examined how individual beliefs about the infectiousness of COVID-19 influence compliance with social distancing. We randomly assigned participants to a control group (where no message was shared) or one of two treatment groups. Those in the treatment groups received a message about the risk of COVID-19 transmission, and were told that they are likely to infect either 2 or 5 other people if they contract the virus.

We found that while individual prior beliefs about the infectiousness of COVID-19 are higher than expert estimates, our interventions partially correct their beliefs. Interestingly, we observed that information interventions may have unintended consequences. In the first experiment, we found that people are more likely to report feeling afraid when exposed to a message emphasising individual risk, suggesting that the personal intervention may cause distress. In the second experiment, we noted that increasing the perceived infectiousness of the virus actually makes people less willing to comply with social distancing.

These results highlight the importance of taking into account potential spillovers (unintended effects) when designing interventions and the need for rigorous evaluations so that we can deliver effective communications about the dangerousness of the virus to the public without unintentionally causing harm.

2. Understanding individual beliefs and attitudes about COVID-19 vaccines in different contexts is important to our efforts in increasing vaccine uptake.

Vaccine hesitancy has been observed in many countries and poses challenges as countries seek to vaccinate enough of their populations to allow for safe reopening. To reduce skepticism and increase uptake, it is important to better understand individual beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours related to COVID-19 vaccines across different contexts.

In collaboration with The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS) and Boston University Questrom School of Business, we conducted a survey with blood cancer patients and survivors in the US, a population that is particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. We found that 17% of respondents were vaccine hesitant, mostly stemming from the belief that the vaccines have not been properly tested and concerns about side effects. Further, we found that those who display vaccine hesitancy are also significantly less likely to practice protective health behaviours (e.g., wearing a face mask).

In addition to contributing to the understanding of vaccine hesitancy among cancer patients, our findings highlight the importance of effectively communicating the risks of COVID-19 infection and the benefits of vaccination in reducing vaccine hesitancy among cancer patients. This information can be shared in many ways and through different channels, including being hosted and regularly updated on a publicly accessible website, as exemplified by Blood Cancer UK. Finally, our findings also show that it is important to increase the diversity of vaccine trial participants so that trial results could reliably generalize to those who are most impacted by the virus.

Our team's research into using behavioural science to combat vaccine hesitancy is ongoing. To better understand vaccine-related beliefs and help increase vaccine uptake in other contexts, we are currently conducting two online survey experiments. First, we are designing and testing behavioural interventions that can help increase vaccine uptake in workplaces (e.g., care homes and companies) in collaboration with the Sandwell Council. This experiment involves asking participants about their specific concerns and reasons to not get vaccinated and then presenting them with tailored, behaviourally-informed interventions that are specific to their stated concerns. By directly addressing the specific reason to not get vaccinated using behavioural framing techniques, we aim to positively influence people’s intention to get vaccinated.

Second, we are working with researchers from the University of Oxford to study how people’s beliefs about serious side effects associated with COVID-19 vaccines influence their willingness to get themselves and their children vaccinated. We will also examine whether adding a statement that frames not getting vaccinated as an active choice increases people’s willingness to get vaccinated.

COVID-19 is an ongoing battle and behavioural science has a crucial role to play—it provides insights that can be used to generate positive behaviour change in a low-cost and scalable way to control the spread of the virus.

You can find more information on our COVID-related projects below. Follow The Behaviouralist on LinkedIn and Twitter to receive updates on our work!

Please have a look at our COVID-19-related projects!